November 7, 2024

Transcript by Gallery and Curatorial Fellow Cat Teo

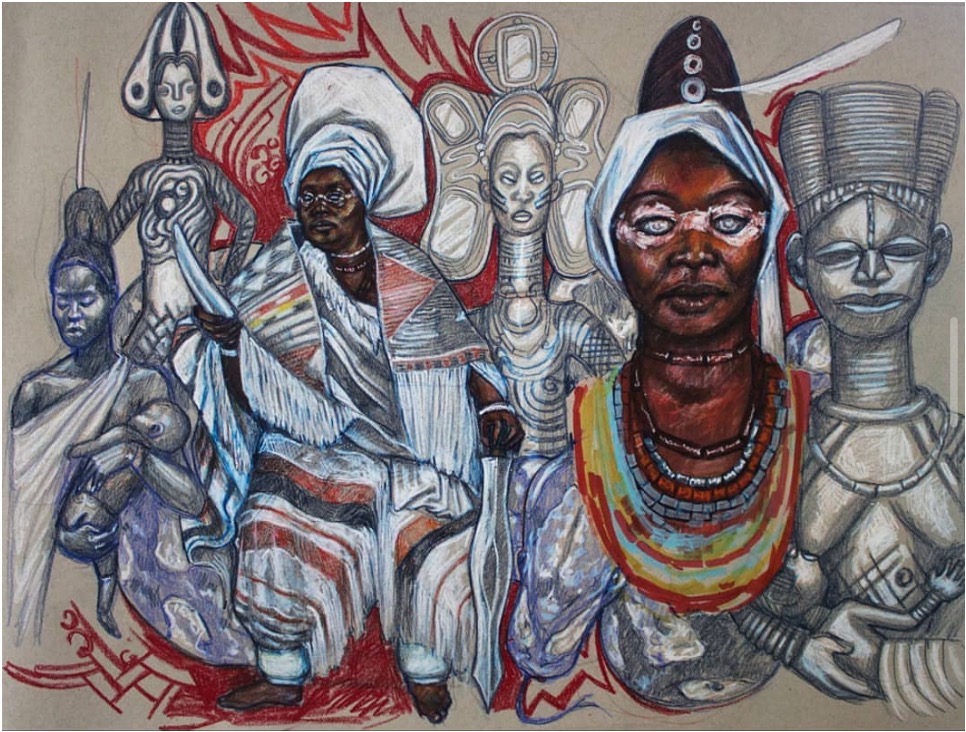

Stephen Hamilton’s Ala, Ale, Anyi is a study that depicts two women in color in the foreground and other woman-like figures in the background in gray. The two women in front are drawn wearing white clothes, headscarves, and beaded jewelry. The figures in the background, also women, are contrasting in looks, drawn in a more stylized manner. In his work, Hamilton investigates the idea of motherhood and feminine potential. In Western cultures, motherhood is seen as a sacrifice and a forfeit of power. A mother, while strong in the aspect of nurturing her children, is also a weak being that holds no real power within society. In Africa, women are understood to have an enormous amount of control and strength within the world since they are the creators of life. Their ability to control the production of people makes them formidable, influential beings: women are essential to the balance between life and death. This ability is not taken for granted and translates into how many cultures in Africa personify powerful beings, such as the Earth.

In many African cultures, the Earth is imagined to be a woman who is a mother; this is a familiar trope the world over. However, within these cultures, she is not personified as a loving, kind force. The Earth is not considered good or bad, she is an ambivalent being. Within African culture the Earth is often referred to as “Mother who cuts with a knife” and “She who eats you in death”. Even though she is ambivalent, she still wields an immense amount of power. This comparison with Earth and women can be seen in how women are thought to be just as capable of destruction as they are of creation. Women being considered ambiguous creatures invites us to understand them as complex beings.

Hamilton expressed that in Africa, you can see women being depicted in art not because they are divine creatures and that is what’s worth portraying, but because artists see them as truly remarkable. In Western Art, women are often represented as sacred and pure. Their innocence and divinity is celebrated and is the reason that they are the center of the art. In many African cultures, women are more ambivalent. They are not born to be a certain way just because they are women.

Hamilton’s work often depicts the vast differences in how women are considered within motherhood across different cultures. In this drawing, the women are not shown to be sacred, ethereal creatures. They are illustrated as women. The references to motherhood in this drawing combined with the way many African cultures think of women furthers this point. Mother’s are not pure, spiritual beings, nor are they devilish creatures. They are ambivalent, sometimes good, sometimes bad. The role of “mother” does not transform them into some sacred, kind, and gentle angel. The women are not only considered ambivalent but they are also thought to wield an immense amount of power. The box that women are often put into within Western cultures does not exist as strongly within African culture. There is no preset expectation that they are supposed to be weak and pure, instead they are powerful and complex.

Western understandings of women rarely put them into this category of powerful, commanding beings. They can often be understood as gentle, soft creatures, yet here Hamilton depicts them in a new light. In Africa, women are understood to be complex and ambiguous – not necessarily good or evil. In what ways can we further our understanding of women beyond the idea of just “good” and “evil”? How does Hamilton communicate this ambiguity within his drawing? Notice the expressions on their faces and the poses. How is this deeply contrasting with the way that Western civilizations characterize women within art?