October 16, 2023

By Gallery & Curatorial Fellows Calla Savelson, Catherine Teo, and Kaitlin Benton

Images Courtesy of Catherine Teo

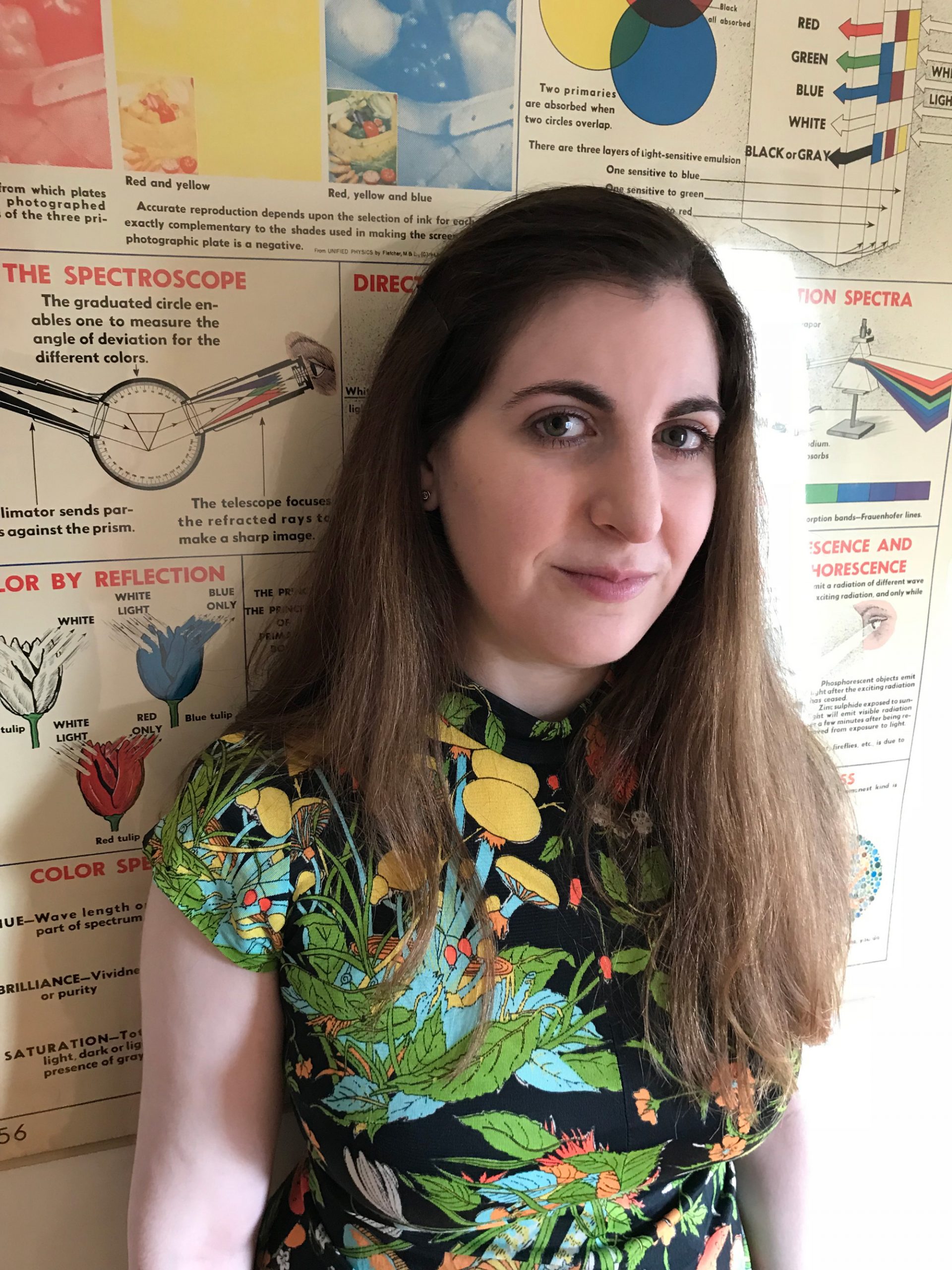

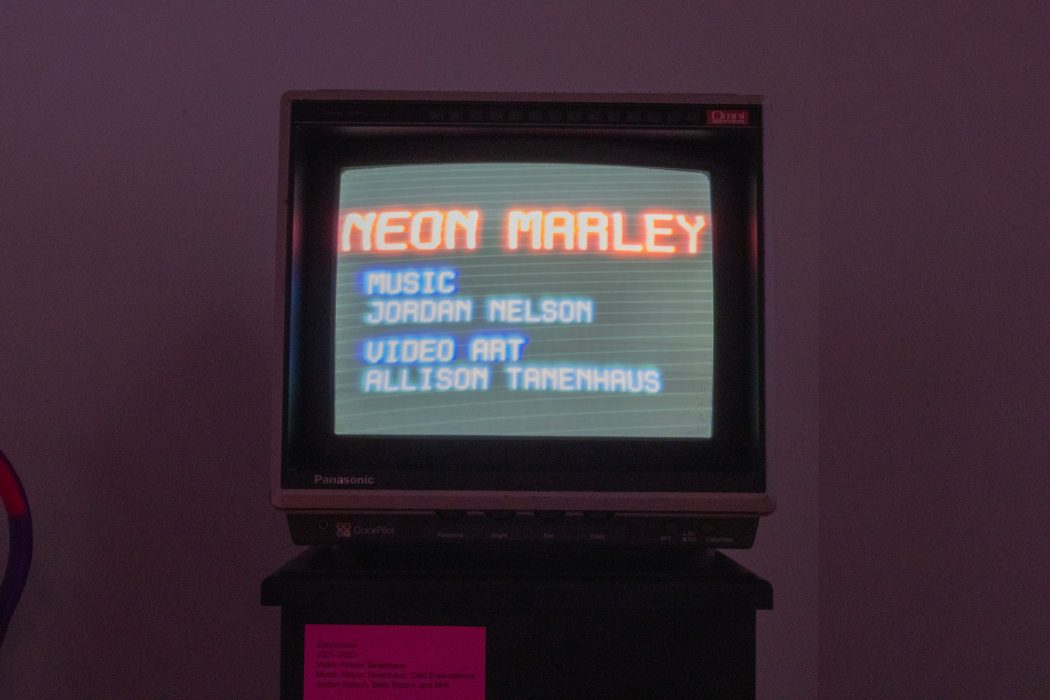

GlitchKraft is a glittering ode to glitch art, the practice of disrupting digital files for aesthetic purposes. Using and misusing consumer software, nostalgic electronics, smartphone apps, and AI, the exhibition’s pixel pushers—all in or with ties to the Boston area—embrace error with perception-bending intention. In an interview with Allison Tanenhaus, a Boston-based digital glitch artist, she pulls us into the psychedelic world of colorful hues and new dimensions.

Calla: Tell us how you got into art and how you got to where you are today.

Allison: From an early age, I was really into reading and writing. This was something teachers liked, so I got pigeonholed and kept at it. I was always the kid at recess who was off in the corner reading (which should not have been encouraged; socializing and playing is very important!). I thought that reading and writing was just my thing, but then little things started coming up. I got really into music and mixtapes, making album covers for people, and making merch for bands I was friends with. I always thought of it as me doing a little favor for someone—I still had this reverence for artists, and was like, that’s not me though, I’m a writer.”

I was an English major, and briefly considered doing something with art and took [art] electives for fun. I knew that I wanted to be creative, but I couldn’t find my medium. None of my work added up to any paradigm shift in my identity. After college, I was doing work as a writer, and I always got asked: are you going to be a teacher or write novels? I was always like, are those really my only options? I don’t remember signing up for that. English is a big language and it seems like there should be more you can do with that. So I ended up going into marketing. I was always drawn to the designers on the magazine staff. I would sit with them as they were working. It was thrilling seeing where they were going to fit a column or where they were going to add a picture.

Around the same time, I was doing comedy writing on Twitter (in the very early days before it became a toxic hellscape). I had a friend in LA who was doing stand up and we would write jokes to each other over email. We started writing comedy and submitting our work, but I was getting frustrated because I was coming up with funny taglines for t-shirts and entering them into Threadless contests and the New Yorker Caption Contest, but they weren’t winning. Twitter for me was a place where I could just put something out there and it’s real. Which seems obvious now, but at the time was kind of revolutionary. But I was still hitting this wall where I was coming up with funny stuff, and then it disappears in a few days because no one’s going to scroll down far enough to see it.

I had been watching my designer friends be able to turn words into art through typography. I started getting into typography as the next step of my writing journey. I started making street art with some of my jokes or more satirical one-liners. I was taking photos of my typography for the early days of Instagram, when filters were new, and just kind of stumbled upon one of these apps that was called glitché, that was, as the name suggests, a glitch app. I remember my dad saw my glitch art and said, “your word art’s fine, but this is really good.” Then I took a really hard swerve where I let go of the writer’s identity and realized I actually can express myself and make art, and I have the tools through trial and error. I wasn’t an art major, and I didn’t take many art classes, but having exposure to the arts, even just through my Twitter work, helped me feel empowered to explore and not give a shit what other people said.

A few years later, I found all these old watercolor paintings I’d done when I was a kid, just for fun, when I wasn’t thinking about having any goal in mind. They were reminiscent of my glitch stuff, just colorful abstractions. I was like, “Oh, was this always in me?” But I just wasn’t that encouraged, and I didn’t have all the tools. I struggled with being able to separate myself from that [prescribed artist identity]. The art world is now more vast and welcoming and has more tools available that you don’t have to have one strict role, you can play around and try different techniques and explore. So [finding the old paintings] was the moment where things clicked into place where I was like, I always was into weird abstract experimentation, but I just hadn’t found my process. I got more confidence in myself and people started calling me an artist, which was so bizarre. In the beginning, it was a process to start to see myself as an artist, where there was always some caveat like, I just do stuff on my phone or I didn’t go to art school, so I’m not an artist. Little by little, as I either gained confidence or just didn’t care anymore, it became, “I’m an artist,” full stop.

Calla: Once you took that swerve towards art, did you ever take any art classes? Or was it all just your own experimentation?

Allison: I’ve taken a few classes, but it was really early on. Originally, in one of my first attempts to bridge the writing with the drawing, I got really into autobiographical comics. I had written all these scripts and these stories. So I took some drawing classes, but it was really laborious. I think that’s something that I really like about digital art; the speed with which you can create, where I’m not just there with my pencil making mistakes and trying to get something specific or achieve realism. Even when I was really into comics, what I liked about it was that I didn’t have to write about what things look like in my writing, because the drawing will do that. With the glitch artworks, you will get the sensation and the vibe, and the more that you can cut back on being didactic, and just bring people into it to create an experience without having to narrate it and dictate it. So I think that’s also been really appealing, but that isn’t something that I learned in a class per se.

I took a painting class and I was just terrible. It was really frustrating, especially as an adult, trying to create and feeling like a beginner and being like, “I’m actually competent in some things, aren’t I? Why does this look like a deranged five-year-old’s painting?” I think a lot of the insecurities came from having an end goal in mind of something representational. It might be if I took some classes now that were more abstract-based, where I didn’t have to have a realistic goal, I might not be as discouraged. Clearly if you see my work, nothing is realistic.

Cat: What does your creative process look like?

Allison: So it totally varies and I think that’s probably a good thing. Pre-pandemic I had done a building wrap, some window cling stuff that was really fun and immersive, some wallpaper for a hotel, and had been hired to do an installation for an airport. Then the pandemic hit and we weren’t doing any more hotel or airport stuff because people weren’t traveling. My process used to be a little more restrictive because I knew that either I was going to be pleasing clients or I had to fit some kind of production specs. Now that I’m doing more video stuff, it can be a bit more free. So it really depends. Am I doing art for myself? Am I doing something that’s music video related? Is it an installation? Am I going to be collaborating with someone?

In the case with the Simmons show, there’s a concept, but there’s a lot of freedom to it, so I don’t really have a distinct process. Sometimes it’s sifting through old clips seeing what I can stitch together. Now that I have a body of work that I have shown a few times, I like to keep making things more difficult for myself. With this show, I’ve gotten really into older technologies and the challenges they have and the way that it makes me crazy.et if I overcome it, I feel all-powerful. Here we have the slide projector and old TVs to fit an aesthetic, and to create some kind of rhythm. If it’s a music video, is it for the specific track? Am I featuring the artist in it? Is it going to be on YouTube? Is it going to be something like in a planetarium where I have to think about where the viewer is in the experience? Is it on a small TV? Is it going to be something black and white or colorful?

If I’m working with portraiture or public domain stuff, I’m trying out techniques on different apps, I’m glitching it out. I’m maybe combining things. If I’m doing album art, I’m trying to get one still. So I don’t have a pat answer. It’s just always this big mess of me being curious and trying to hit that sweet spot, even if it’s a moving target. So I think there’s just a lot of exploration and satisfying my own curiosity. And hopefully if I’m being hired for something, satisfying whoever it is that’s paying me.

Calla: Would you mind talking a little bit more about how you use AI? What programs do you use and how do you decide which steps AI takes part in?

Allison: AI is a really big topic. The way I treat AI and glitch is in a way where I think of myself as collaborating with technology, but in a way where it’s not taking full authorship. In my earlier days, I was going to be giving a glitch workshop and my mom was like, don’t give away your secrets. I was like, first of all I’m not into gatekeeping, but also if I’m purely doing something step by step, or it’s just a machine doing it, and someone else can learn my techniques and do the same thing, then I actually don’t have any creative agency. If I’m bringing my own special sauce, then I can share my techniques because it’s not going to be the same as what someone else is doing. That’s kind of my barometer. If I look at something and it’s identifiable as mine then I can take ownership of it. A lot of it has to do with creative prompting. Many people using AI are trying to achieve a mainstream professional style, which I have zero interest in.

I try to use AI in a way like glitch art, where I’m almost distorting its purpose or messing with my material to create something odd that has a weird perspective, uncanny feelings, and plays with color. I try to play with a lot of juxtaposition and contrast. With AI, a lot of what I’m doing is almost trying to break its brain, where I’ll give it a lot of different prompts that have stylistic overtones or different eras, but I’ll throw in ripples or plumes—where you’re giving it stuff to do and it’s like, “What the hell is this?” It doesn’t have a frame of reference in reality, so it can’t just spit out something it’s seen, it does this weird synthesis. That’s what really gets me excited, when I can make something that has unexpected elements that are nonsensical, yet have some semblance of logic to them. I’ve seen a lot of AI that’s really gory and I’m like, “No! I wanna make stuff that’s fun!” In my art I avoid strobing, stuff that’s really too intense. It should have this kind of organic quality, it should breathe, it should be soothing in a pacifying kind of way where you sync up with it and get lost in it.

I’m still struggling with how to use AI in a way that seems original and isn’t just derivative. I try to give it some kind of original twist so that it has my personality infused into it. There is so much more that goes into it, but that’s at least my approach for now. I try to take one additional step either in how I contextualize it, how I edit it, how I add stuff to it that gives it my own twist. I don’t think it’s ever just like “I pushed a button!” there’s gonna be some input from you. I mean there’s all kinds of AI things I’ve been using for years, like spellcheck or autocorrect. AI isn’t just art theft, it’s more fun than that, and also more helpful.

Cat: How do you reconcile with the anxieties surrounding AI?

Allison: Yeah, so actually there’s not a ton of AI in the show. It was tough in the beginning, I had to have a lot of chats with myself and with friends where I was like, “Where do I stand on this? What is ethical? Is this going to be this tool that destroys humanity?” First of all, I’m using it for fun, so I’m not trying to be destructive! I don’t feel like I’m directly ripping off anybody else’s work. I also don’t put in any specific artists’ names so I’m not trying to copy them.

I don’t think I’m going to move the needle in terms of “Does AI destroy our way of life?” I think it’s just here, and as long as I individually am trying to be conscious and ethical about it, then hopefully I’m not adding to the harm. At least I can make cat art with it. I’m like, terrible things are going to happen anyway and terrible people make decisions with power. It’s just one more tool in the arsenal of potential human destruction.

Kaitlin: How does this exhibition and the work of glitch discard traditional modes of representation? Do you strive to create some sort of new visual language through distortion? Is it something meant to be understood or experienced?

Allison: I don’t know if I’m striving to create a new vocabulary, a new art expression for everyone per se, like a new genre. But for me, it was a new way of expressing myself. I fortunately did not have to go through my youth with social media. I want to be in control of my own representation. A lot of the stuff that I do when I glitch is use photos of me or stuff from my life. It actually is autobiographical; you just wouldn’t know it. So I think the appeal for me is pulling from my life and having it be in a new form. It’s a big question. I don’t necessarily have all the answers, but for me fighting against imperfection and having more ownership over how I present myself and what I put out there and how I can disguise it and kind of fashion it in my own way has been liberating. Being able to create your own spaces and output, where you are acknowledging the landscape and state of tech, having your own autonomy built-in is good.

Kaitlin: Is there anything specific about your artwork that signifies to the viewer that it is yours/your signature work?

Allison: Definitely cats. In terms of colors and patterns. I love bright colors and also like weird unexpected palettes where it almost could be ugly; you wouldn’t think to put those colors together. I really like stuff that takes your brain and massages it. I think about that ride at Universal Studios, where you are in your own pod and there’s a video where it moves you a little bit as you go along, so you have your own mini roller coaster with a video involved. That’s what I want to do, to give you these sensations of movement and you’re being brought along, but you don’t have to be tensing up because it’s not going to strobe or have a quick cut that is jarring. I really want it to be something where you can just groove.

I think that’s where I got into doing more stuff with music. Once again, my dad pointed out when I started doing video stuff, he was like, “Oh I love your dancing glitches.” I was a dancer—not a very good one—but I used to dance and when I am doing my glitch art and how I know it is flowing is when I can hear music moving with it. There has to be a flow to it, and if it is too herky jerky, it doesn’t feel like me. So I wanted it to be somewhere where you can get lost in. I try to create things that satisfy my inner child and that express it because I wasn’t able to make art at that time. Also a lot of it looks very vintage-y because of this yearning to be traveling through time, to create, to experience things you didn’t have that are entirely of your own making.

Calla: I had a question about this combination of new and old because glitch art is this very new medium, but you use all of these old CRTs and also these retro, vintage images. Now I am also thinking about it in terms of childhood versus adulthood. Is there anything else you want to say about that?

Allison: I’ve been dabbling with that over time, with the CRTs and especially with the AI installation. The way I approach glitch now is a next generation of art practice. I think a lot about what is available to me because that’s what’s happening in the world now. Then, how can I make mischief and do it wrong? So with those apps, I could have Facetuned myself and instead I am making it super weird, colorful, bizarre, and unrecognizable.

They [objects from the past] still exist; who are we to say you have to have lived through something to be able to have a connection to it? We have the privilege of having access to eons of human creation, so we should be allowed to pick what inspires us even if we weren’t there.

With the old technology as well, I think there is this complexity within me where I am trying to salvage things and make something cool out of them. Even with CRTs, I find them on the side of the road or someone is getting rid of them, but they still have value. There is a way you can use them and embrace them to make something beautiful that can be shared, as opposed to trashing it because it is not the newest TV. I think there is this element of me trying to feel like making something beautiful out of detritus or recognizing usefulness in something people might overlook.

Calla: Lastly, I was wondering about the community aspect of your work. You do a bunch of these GlitchKraft and Haus Party shows and they’re always with other artists. For this show, we had an opening reception which was a party and brought all these people together. How does this community aspect play into your work and ideology and why do you think it’s important to be bringing people together?

Allison: There’s many different pieces to this answer. One is that it’s just fun, on the simplest level. Beyond that, when I started making glitch art, I was doing it in isolation and when I would look up stuff about glitch online, there were a lot of people who were very technical who have been doing it for years and could explain analog signals in a way that I could not.

I’ve been helped along in many different aspects of my life by having mentors and having people who believed in me, so it’s just part of my ethos to create a community and learn what other people are doing—learning from them, learning with them, and giving them opportunities.

I don’t want to be the only person who benefits, otherwise I wouldn’t even show my work—it would just be purely onistic. I want it to be something where other people are exposed to new ideas, techniques, and get inspired. Art teachers can make their own art, it’s not like if you teach someone how to make art you no longer have a talent or identity. I think bringing other people along, mentoring, and collaborating makes you learn more about opportunities and techniques, and discover new commonalities.